Introduction

The resurgence of interest in process philosophy, particularly through the work of Alfred North Whitehead, has invited renewed attention to metaphysical frameworks that emphasize becoming, relation, and creativity over static substance and immutable form. Whitehead’s cosmology breaks from classical metaphysics by grounding reality not in fixed essences but in actual occasions of experience—momentary events of becoming that collectively constitute the world. Yet, despite this radical processual foundation, Whitehead preserves certain structural holdovers from more traditional ontologies: namely, the existence of eternal objects as timeless potentials, and a non-temporal God who orders these possibilities and lures the world toward value.

This essay questions whether these elements—eternal objects and the primordial nature of God—are truly compatible with Whitehead’s own ontological principle, which asserts that all causes must be actual. If eternal objects are not actual, and if God’s ordering of potentiality stands outside time, do we not risk reintroducing precisely the kind of metaphysical dualism that Whitehead otherwise seeks to overcome?

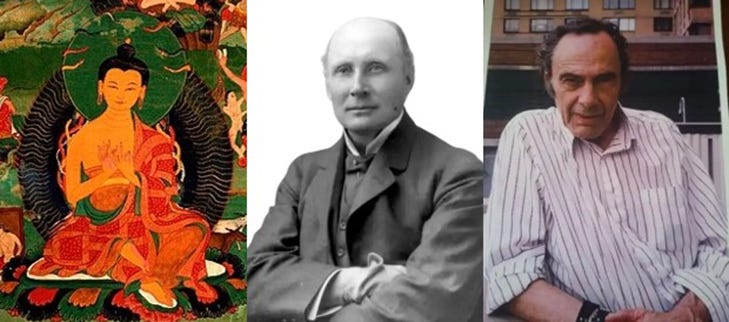

Drawing on the work of Eugene Gendlin and the Buddhist Madhyamaka tradition, I propose a revision: a process-relational metaphysics in which potential is not pre-given but emergent, and in which divinity is immanent to the unfolding of actuality, not a separate or prior source of order. Gendlin’s concept of the implicit—a non-conceptual, felt sense of unspoken complexity—offers a model of potential that arises within and through process. Likewise, Madhyamaka’s radical critique of intrinsic nature (svabhāva) and its principle of dependent origination resonate with the idea that meaning, form, and even possibility are co-arising rather than pre-existent.

In what follows, I will first lay out Whitehead’s metaphysical architecture and then examine the internal tensions it generates. From there, I will articulate a revised framework in which actuality and potential are mutually generative, and in which divinity is recast as the world’s own immanent capacity to feel, respond, and create. The goal is not to reject Whitehead but to take his most powerful insights—relational becoming, creativity, and value—and carry them forward beyond the residual structures of timeless order.

Whitehead’s Metaphysical Architecture

At the heart of Whitehead’s philosophy lies a bold reorientation of metaphysics around the primacy of process. He replaces the static, substance-based metaphysics of Western tradition with a world composed of actual entities (also called actual occasions)—finite events of becoming that constitute the only fully real things. Each actual entity arises through a process called concrescence, in which it synthesizes past influences, integrates potentialities, and perishes into objective immortality, becoming part of the world for future occasions to inherit. This vision affirms the deeply relational and temporal nature of reality: everything is constituted by its relations to others, and nothing endures as a self-identical substance.

Alongside actual entities, Whitehead introduces two other ontological categories: eternal objects and God. Eternal objects are pure potentialities—forms or qualities like “redness,” “symmetry,” or “grief”—that can be ingressed into actual occasions, shaping how they become. Unlike actual entities, eternal objects are not themselves events; they do not occur or perish. They are abstract, timeless possibilities that must be ordered and made relevant to each occasion’s context.

This is where God enters Whitehead’s metaphysical scheme. Uniquely, God is described as a non-temporal actual entity—one that does not undergo concrescence in the same finite, perishing manner as other actual occasions. God possesses two natures: the primordial nature, which envisions all eternal objects in their potentiality and provides a graded valuation of them; and the consequent nature, which feels and integrates the becoming of the world. The primordial nature of God is Whitehead’s solution to the problem of order: without a unifying vision of possibility, the infinite multiplicity of eternal objects would lack coherence. The consequent nature, on the other hand, ensures that God is not aloof but immanently involved, taking into account all lived experience.

Whitehead’s ontological principle asserts that “actual entities are the only reasons,” meaning that nothing can exert causal efficacy unless it is actual. This principle is foundational to his system, ensuring that causality is immanent rather than transcendent, and that all influence must be rooted in some form of experiential becoming. Yet it is precisely here that a tension emerges. Eternal objects, though causally influential, are not actual. The primordial nature of God, though responsible for the ordering of potential, is described as non-temporal and unchanging. These elements appear to exist outside the world of becoming that Whitehead otherwise claims is all that is real.

This internal strain—between the radically relational and temporal foundation of his metaphysics and the lingering elements of timeless order—sets the stage for a revision. In what follows, I will critique the coherence and necessity of eternal objects and the primordial nature of God, and offer an alternative rooted in the emergent, processual nature of potentiality itself.

Critique of Eternal Objects and the Primordial Nature of God

While Whitehead’s metaphysics begins with a strong commitment to process, relation, and temporal becoming, his inclusion of eternal objects and a non-temporal deity introduces elements that subtly reinstate a static metaphysical background. These components, though carefully constructed, risk undermining the very dynamism that Whitehead seeks to affirm. When examined closely, both eternal objects and the primordial nature of God introduce tensions with Whitehead’s own ontological principle and with the logic of a truly emergent cosmos.

Eternal objects are defined as pure potentials for definiteness. They are not themselves actual; they do not undergo concrescence, perishing, or temporal change. And yet, they are said to ingress into actual entities, shaping how those occasions become what they are. Whitehead maintains that without eternal objects, novelty would not be possible—there would be no form, no contrast, no aesthetic structure to the world. However, this premise raises several ontological and epistemological concerns.

First, there is the problem of causal efficacy without actuality. If eternal objects are not actual, how can they exert any influence on the becoming of actual entities? This seems to contradict Whitehead’s own ontological principle, which insists that all real causes must be actual. Nothing, Whitehead says, should “float into the world from nowhere”—and yet eternal objects appear to do precisely that. Second, treating potentiality as a fixed, timeless domain contradicts the processual creativity that Whitehead otherwise affirms. If all possibilities already exist “out there,” then novelty becomes mere selection among pre-given options rather than the invention of new affordances. Creativity is reduced to recombination rather than emergence. Finally, this dualism between actual entities and eternal objects risks reintroducing a Platonic or scholastic metaphysics—one that splits the world into temporal becoming and timeless being. Despite Whitehead’s efforts to harmonize these domains, the division persists, and with it, the metaphysical baggage he sought to leave behind.

The case of God’s primordial nature raises similar concerns. In Whitehead’s framework, God is a unique actual entity—unlike any other—whose primordial nature eternally envisions all eternal objects and provides a graded valuation of them. This function is intended to offer coherence and order to an otherwise infinite field of potentiality. But this solution generates a second tier of metaphysical tension. God is said to be an actual entity, yet not one that exists in time or undergoes change in the same way as other actual occasions. This idea of a non-temporal actual entity is internally inconsistent. If to be actual is to become, to feel, and to perish, then how can God be actual without undergoing any of these defining features?

Moreover, the notion that God assigns value to eternal objects outside of time introduces a fundamental disconnect between potentiality and context. If meaning, novelty, and value emerge from the relational structure of a moment, then how can their value be fixed in advance? This implies a kind of omniscient pre-evaluation that is at odds with the very principles of emergence and relational interdependence. Finally, by positing a divine being that pre-structures the field of possibility, Whitehead’s metaphysics risks reverting to a top-down model of cosmological order. Even if his God is not omnipotent or coercive, the schema still relies on a transcendent architect of form—an echo of classical theism, softened but not dismantled.

These problems are not merely conceptual artifacts; they point to a deeper contradiction between Whitehead’s desire for a thoroughly relational, emergent metaphysics and his residual commitment to timeless structure. If we take Whitehead’s own principles to their full implications, we are led to question the necessity of pre-existent potentials and divine ordering altogether. What becomes necessary is a revision: a vision in which actuality itself gives rise to new potential, and in which divinity is immanent—not as a separate entity—but as the world’s felt capacity to respond, deepen, and transform through becoming.

Revising the Schema: Potentials as Emergent

If we are to remain faithful to the heart of process philosophy—namely, that becoming is primary, and that all causality and structure must arise from actual occasions themselves—then the notion of eternal objects as pre-existent, fixed possibilities must be rethought. Rather than presuming a timeless domain of pure potential, we can reconceive potentiality itself as something that emerges from the interactivity and depth of actual occasions. In this view, potentials are not selected from a transcendent inventory but are invented in and through the very process of becoming.

Each actual occasion, in its process of concrescence, not only integrates the felt influences of the past but also gives rise to new relational configurations—new affordances, new contrasts, and new ways in which future occasions might become. The actuality of a moment is not a closure of possibility but the opening of novel pathways. Potentials, in this sense, are not static ingredients waiting to be chosen; they are dynamic outcomes of relational complexity. This transforms the metaphysical role of potentiality from a background condition to a processual function—an activity internal to the becoming of actual entities themselves.

This conception dissolves the need for eternal objects as a separate ontological category. What we previously described as “forms” or “pure qualities” can now be seen as virtual dimensions of particular relational contexts. The potential for “redness,” for example, is not an abstract form floating outside experience, but a differential quality that emerges within certain perceptual and physical conditions—conditions which themselves are generated by past actualities. Similarly, complex potentials like “democracy” or “grief” are not eternal essences but historically and relationally emergent structures of significance that become thinkable only through the unfolding of particular material and cultural actualities.

By this logic, the entire field of potentiality is cyclically and recursively generated. Each moment of becoming transforms the field of the possible for future moments. This reflects a deeper metaphysical symmetry between actuality and potentiality: rather than occupying separate domains, they are mutually implicated. Actualization does not merely exhaust potential; it creates further potential, and that potential, in turn, conditions future actualizations. Potential is not the prior condition of becoming—it is its residue and ripple, its generative horizon.

This reconception not only resolves the internal tensions in Whitehead’s system, but also aligns closely with Eugene Gendlin’s work in A Process Model, in which the implicit functions as a felt but unformed background of meaning and movement that is shaped and reshaped through each act of carrying forward. In Gendlin’s terms, the process of experiencing never merely enacts what was already given; it transforms the space of what can next occur. Likewise, in this revised schema, the metaphysical space of potential is always in flux, always being reconstituted through experience.

Such a view also resonates strongly with Madhyamaka’s principle of dependent origination. In rejecting the idea of inherent essence (svabhāva), Madhyamaka affirms that all phenomena—including potentials—arise in dependence upon causes, conditions, and conceptual imputation. There is no separate realm of fixed possibility underlying events; possibility and actuality are co-arising and co-defining. To say that potentials are emergent is thus not to deny their reality, but to deny their independence. In both Madhyamaka and this revised process metaphysics, the world is not built on a pre-given metaphysical scaffold, but is self-organizing through relational unfolding.

In this revised schema, we no longer require a timeless deity to manage or order a fixed field of eternal objects. What we need instead is a metaphysics capable of recognizing that potential is always the child of actuality, and that the world, in its ongoing becoming, is the true wellspring of novelty. It is to this vision of divinity—as an immanent, felt responsiveness within process—that we now turn.

Reconstructing Divinity: From Entity to Felt Field

With the rejection of fixed potentials and non-temporal ordering, the metaphysical role of God in Whitehead’s system must also be reimagined. In his original formulation, Whitehead preserves a version of classical theism: God as the unique actual entity who unifies potentiality and lures the world toward value. Even though Whitehead’s God is dipolar—primordial and consequent, abstract and relational—the notion of a pre-existent, ordering subjectivity remains. But once we understand potential as emergent from the flow of actuality itself, the need for a distinct divine entity that structures the field of possibility disappears. What remains is the felt depth of the world’s own self-organizing creativity—a kind of divinity not apart from process, but immanent within it.

In this revised vision, divinity is not a being but a field—a pervasive, felt responsiveness within the web of becoming. It is not an entity who chooses or orders, but a depth dimension of experience itself: the world’s intrinsic openness to meaning, resonance, and transformation. This notion of divinity is processual, not personal; it is not a subject watching or willing the world, but the world’s capacity to feel itself, to deepen its interrelation, to orient toward richness without requiring external guidance.

Eugene Gendlin’s notion of the implicit provides a powerful conceptual bridge to articulate this view. For Gendlin, the implicit is not a static background, but a dynamic, experiential richness that exceeds any formed concepts. It is the “more-than-formed” that precedes and exceeds articulation, and which guides further unfolding. Importantly, it is not a formless chaos—it is structured, but its structure is not fixed. It functions like an unspoken logic within experience that carries forward, reconstituting what is possible through what has actually occurred. In this sense, the implicit is very much like the emergent potentiality we have attributed to actuality: a background that is continuously shaped by—and shaping—the process of becoming.

Reimagined in this way, divinity is the world’s own implicit: the felt, immanent coherence within experience that draws it forward without predetermining its shape. It is not external to events, but present in each actual occasion’s capacity to integrate, respond, and open new lines of development. The “lure toward value” is not a divine act of persuasion from without, but a felt orientation within each becoming, arising from the internal depth of relation.

This perspective finds further resonance with Madhyamaka thought. Nāgārjuna’s denial of inherent existence (svabhāva) extends not only to things but also to causes, effects, and even emptiness itself. There is no ultimate ground outside the play of interdependence—no God, no eternal law, no fixed realm of forms. And yet, far from denying the meaningfulness of becoming, Madhyamaka affirms that value and coherence arise precisely because nothing stands alone. Everything is what it is only through its participation in a web of mutual emergence. The divine, in this context, would not be a separate actor, but the sheer fecundity of interdependence itself.

In both Gendlin and Madhyamaka, we find visions of reality that reject metaphysical hierarchy while affirming a depth that is neither static nor arbitrary. Meaning, form, and potential arise not from a timeless order but from the generative tension within becoming itself. To call this divine is not to anthropomorphize it, but to name the felt immanence of value within the process of change. It is the sense that the world, in becoming, is not merely churning but creating—and that every act of becoming is a creative act of implication.

Thus, in this reimagined metaphysics, we do not abandon the divine; we transform it. We move from a theology of transcendence to a theology of emergence, from a divine subject to a divine field, from a God who orders possibilities to a world that sings itself into further coherence, moment by moment.

Toward a Fully Immanent, Process-Relational Cosmology

Reframing potential as emergent and divinity as immanent allows for a truly relational cosmology—one in which becoming is not guided by a pre-established order but unfolds through the recursive creativity of actualities themselves. This is not simply a metaphysical revision, but a reorientation of how we understand causality, value, and agency. The world is not the execution of a plan; it is a fabric of lived responsiveness. Meaning arises not from fidelity to a transcendent blueprint, but from the intensification of relation.

In this revised schema, there are no metaphysical absolutes outside the flow of time—no eternal forms, no primordial valuations, no overarching divine intentionality. Instead, the structure of reality is generated from within: each actual occasion carries forward a residue of its past and projects a horizon for future actualizations. This horizon is not fixed; it is the product of the occasion’s unique relational position and experiential depth. Potential is no longer the ontological precondition of actuality, but its consequence and continuation. Becoming is not the realization of latent possibilities, but the generation of new affordances through enactment.

Such a cosmology supports a fundamentally different approach to ethics and value. If possibilities are not pre-given, then value is not a matter of conforming to eternal ideals, but of deepening relational coherence within the particularity of each moment. The good, in this view, is not an abstract universal but a felt resonance, an emergent harmony that arises through attentive participation in the unfolding of situations. This grounds an ethics of responsiveness rather than command—an ethos of attunement rather than obedience. Responsibility is not the burden of fulfilling external standards, but the act of contributing creatively and wisely to the open-ended evolution of shared experience.

This vision also redefines subjectivity. In classical metaphysics, the subject is the bearer of identity and agency, situated against a background of objective structure. In this process-relational cosmology, however, subjectivity is not a pre-given essence but a function of participation. Each subject is a node of perspective, a local integration of world-affecting and world-affected processes. The self becomes a momentary emergence of relational intensity, not an isolated knower but a site of world-making. To be is to be implicated—to be shaped and shaping, made and making, in the continual reciprocity of unfolding.

Moreover, this cosmology undermines the traditional divide between the natural and the divine. Creativity, in this view, is not a supernatural power but the very dynamism of the cosmos itself. There is no ultimate outside—no source of meaning or value apart from the interrelated becoming of the world. And yet, this does not flatten or secularize the cosmos. Rather, it opens the possibility of a sacred immanence, a world suffused with value not because it reflects a transcendent order but because it is the process by which value arises. The world—and the human being—becomes divine not by virtue of its origin but by virtue of its capacity for transformation.

This process-relational framework converges powerfully with both Gendlin’s process model and Madhyamaka’s dependent origination. In Gendlin, the carrying forward of experience is always more than what has been formed—it exceeds conceptualization, yet is deeply structured by felt meaning. In Madhyamaka, form and emptiness co-arise: nothing has fixed nature, yet nothing is nihilistically void. Meaning, value, and form emerge in mutual dependence, not from a metaphysical foundation. In both, we find a vision of process that is not chaotic, but patterned; not predetermined, but ordered through emergence; not empty of value, but full of immanent responsiveness.

The result is a cosmology without metaphysical hierarchy—a world that is not governed, but self-unfolding. Divinity is no longer a distinct entity but the world’s own capacity to deepen, to intensify, to feel. Potential is no longer a metaphysical background but the shimmering edge of every event. In this view, every actuality is a creative act, every relation a site of implication, and every moment an invitation to participate in the continual reweaving of the cosmos.

Conclusion

This essay has sought to carry forward the most compelling insights of Whitehead’s process philosophy while also addressing the deep tensions it inherits from older metaphysical structures. Whitehead’s commitment to becoming, relation, and creativity marks a decisive break from classical substance ontology. Yet his reliance on eternal objects and a non-temporal God reintroduces elements of transcendence that stand in tension with the radical immanence his system otherwise affirms. By examining these tensions and drawing on the complementary insights of Eugene Gendlin and the Madhyamaka tradition of Buddhist philosophy, we have proposed a metaphysical revision: one in which potential is not pre-given but emergent, and in which divinity is not separate from the world but immanent within its becoming.

In place of eternal objects, we have described potentials as the recursive byproducts of actualization—novelties that arise through the very act of becoming and shape what can next occur. Gendlin’s concept of the implicit provides a vocabulary for this view, emphasizing that meaning and structure are carried forward rather than imposed from above. Madhyamaka’s doctrine of dependent origination reinforces this insight, showing how all things—including value and possibility—arise without essence, through relation and context.

Likewise, instead of a divine entity who pre-structures the field of possibility, we have reconceived divinity as a processual depth within the unfolding of the world itself. This is not a God outside time, but the world’s own capacity to feel, respond, and orient toward greater coherence. Divinity, in this view, is the implicit call of the cosmos as it deepens itself. It is not a subject, but a field; not a planner, but a resonance; not a ruler, but a rhythm.

In weaving together these strands—Whitehead’s process ontology, Gendlin’s felt intricacy, and Madhyamaka’s relational emptiness—we arrive at a metaphysical vision that honors the irreducible creativity of the cosmos. This is a world without metaphysical guarantees, but not without direction; a world without eternal structure, but not without order; a world without a transcendent ground, but full of immanent meaning.

Such a vision offers more than a metaphysical theory—it offers a lived orientation. It invites us to listen for what is carrying forward in each moment, to feel the implicit contours of possibility arising from within the communion of relations, and to participate—intelligently, humbly, and creatively—in the ongoing becoming of the world.

Fascinating Aaron, I too also was very interested in the Whitehead reconciliation exercise albeit with a different integration flavor!

This combined with the complexity work makes us very like-minded folks!

I tried to do a preliminary reconciliation between Whitehead and Markov blankets!

https://x.com/tomer_solomon/status/1794876746195439624?s=46&t=sgJxM3ppiWW0nc4pGeCJHg